Most people don’t know it, but Wisconsin is home to the largest processor and exporter of kidney beans in the world: Chippewa Valley Bean in Dunn County.

Kidney beans are a specialty crop, not yet farmed at the same scale as corn or soy but with the potential to help farmers expand their crop rotation and increase soil health. Chippewa Valley Bean has plans to expand or repurpose 30,000 acres of Wisconsin farmland for growing kidney beans. To do so, the company needs the technology to lower the risk for farmers, particularly in Wisconsin’s Central Sands Region where growing crops can be water-intensive and unpredictable.

Faculty and students at UW-Stout are using mathematics to help Chippewa Valley Bean and its growers reach their goal. Last summer, Professors Keith Wojciechowski and Tyler Skorczewski launched the Predicting Crop Per Drop in Sandy Soils project, with funding from the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin.

Their goal is to develop mathematical models for growing kidney beans — like those that exist for large-scale crops — that will help farmers increase their crop yield and decrease their water usage.

Anna Hansen and Audrey Williams, both UW-Stout sophomores majoring in applied mathematics and computer science, were hired to work with the professors last summer. The students conducted a literature review, coded algorithms in Python, conducted a parameter study, and collected and analyzed data. During the process, they worked with a team of agronomists and growers using mathematics, statistics and computer science to optimize water-use efficiency for growing a crop.

“My favorite part of conducting this research was learning that math research is not just sitting at a table doing math every day,” Hansen says. “Some days we were out in a kidney bean field talking to farmers with decades of experience farming kidney beans. Other days we were at a farming equipment conference called Farm Tech Days in Marshfield, Wisconsin. If we didn’t have experience in a specific area, we would go to professors in other departments at Stout. It really surprised me how much interdisciplinary work was involved!”

Williams says her favorite part was presenting their research at the Chippewa Valley Bean ownership and agronomy meeting and at a poster session for community members held at the Raw Deal in Menomonie, Wisc.

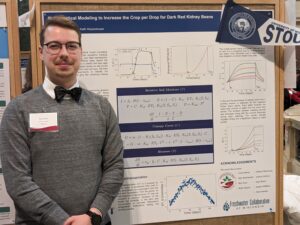

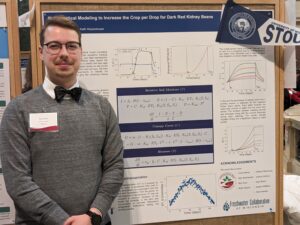

The summer collaboration worked so well that the professors applied for an additional grant to hire an intern to expand upon the work. Noah Royce, a double major in applied mathematics and applied physics, says he was initially hesitant to work on the project because he knew nothing about plants or agriculture, but he wanted to challenge himself. In joining the team, he added functionality to the model and used computational methods to run various watering scenarios that will help identify how to better predict the best frequency and amount of water need to help ensure optimal kidney bean growth.

“We’re looking at the life story of a kidney bean, and farmers want that story to be as boring as possible!” Royce said in describing the project at Research in the Rotunda, which took place at the state capitol in February.

Not only did the Crop per Drop Project provide valuable training to students, but it has led to collaborations among faculty who normally wouldn’t work together. For example, two computer science faculty members built sensors and drones to collect data via Wi-Fi. Wojciechowski and Skorczewski also connected with UW-River Falls faculty to test growing kidney bean plants in their greenhouse. In addition, Wojciechowski says, he can now bring the project into his classroom as a case study to show students how they can apply mathematics to agriculture.

And the partnership with Chippewa Valley Bean is just getting started. Wojciechowski will work for the company while on sabbatical, using applied mathematics to determine where beans are most at risk during growing and processing, develop efficiencies in their processing plant, analyze irrigation practices, and develop a planning plan with field maps so the company can collect data during harvesting.

“Getting the Freshwater Collaborative funding helped us see how this collaboration could work. This project allowed us to start the relationship,” he says. “They liked it and they want to do more. It’s become more than a corporate partnership.”

He plans to bring more students into the research this summer. A group of growers with Chippewa Valley Bean are letting them install temperature and moisture sensors in their fields so the research team can collect real-world data over the next two years. That data will help fine-tune the models. The resulting precision agricultural tools will lower the economic risk for growers who want to expand into kidney bean crops.

Charles Wachsmuth, vice president at Chippewa Valley Bean, says not only will the research help their growers be more efficient, but it will help the company as a whole address sustainability, which is important to their customers.

“The Crop Per Drop Project research is a game changer for Chippewa Valley Bean,” he says. “The ability to share new water management practices with our growing partners has long-term implications as we begin to look at a future with restrictions on normally abundant resources. Not only is this important for our growers, but partnering with UW-Stout on a true sustainability project is important to our customers as well.”