As a child in Chaska, Minn., Madeline Behrens loved rocks and minerals, animals and being outside, but her passion for the environment went dormant in high school when her focus changed to computer sciences courses.

She enrolled at Minnesota State University, Mankato, as a computer science major but quickly realized a career behind a desk wasn’t for her.

“It didn’t spark any joy in me,” says Behrens, who began looking at other options. “Environmental science and earth studies popped out at me. Reading through the classes sparked my passion for the environment again.”

She switched her major second semester. The following fall, a biology professor shared a flyer about summer internship opportunities through UW Oshkosh, which were supported by a Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin grant. Behrens was intrigued and reached out to Greg Kleinheinz, professor and director of UW Oshkosh’s Environmental Research & Innovation Center (ERIC), to learn more.

“It sounded really cool. It would get me fieldwork and lab experience,” she says.

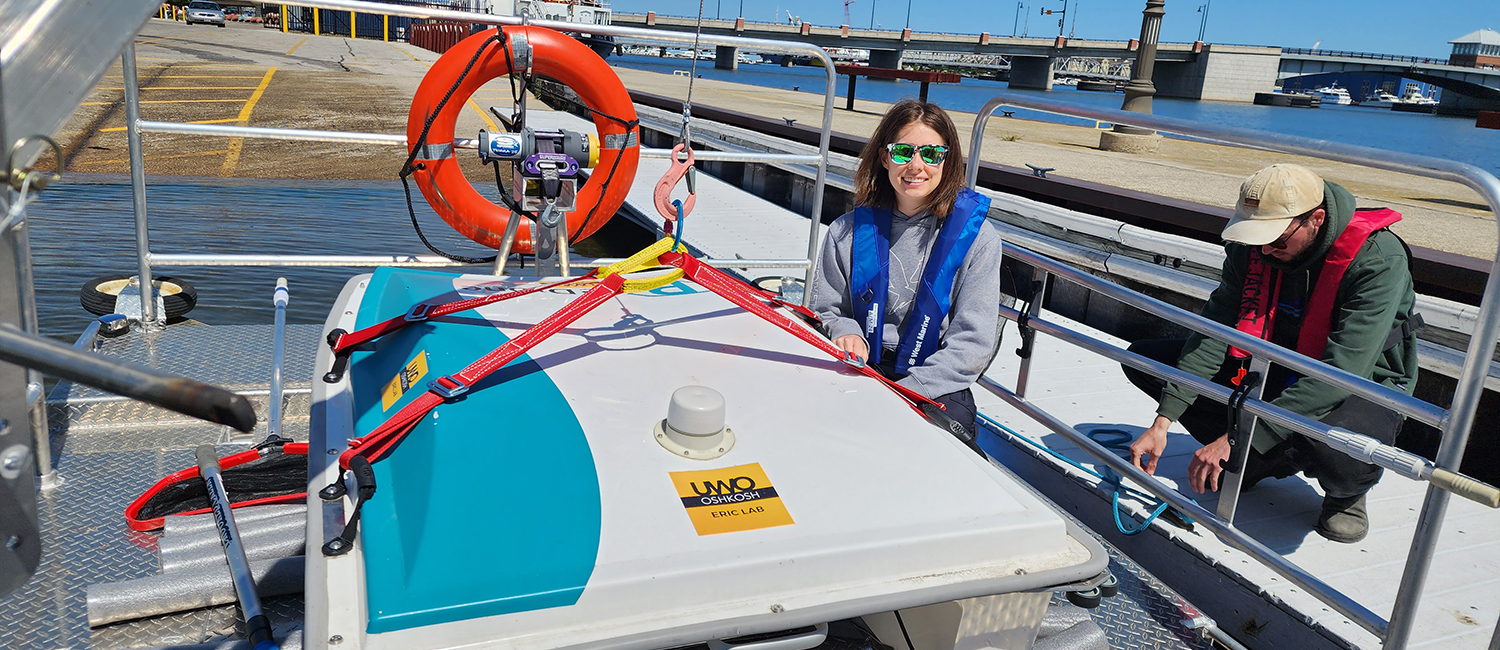

Behrens chose to intern with the marine debris and water quality monitoring group in Door County. She spent the summer with a team of six students, collecting water samples at about 40 beaches. They recorded E. coli levels and worked with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to put out advisories and beach closures when necessary. She also conducted well water testing for the public.

Behrens also spent time on the marine debris mitigation boat. The students removed about 6,300 pounds of trash, ranging from small plastic pieces and shotgun wadding to large items such as stoves, dishwashers, trashcan lids, and giant tractor tires.

The debris the students removed from Door County is just a fraction of the trash that makes its way into the water every season. Certain areas in Green Bay trapped large amounts of garbage daily. Behrens says it was sometimes disheartening to spend hours cleaning an area only to find more trash the next day, but overall, she felt good about her job.

“Someone needs to clean up debris to give people an idea of how much trash is in the water. Seeing the pictures and hearing the numbers of trash pulled from an area around you establishes more of a personal reason for caring about the environment,” she says. “One of the most important steps in the process of marine debris cleanup is bringing awareness to people. If people know the environmental effects of marine debris, maybe next time they will think twice before dumping trash off the side of their boat.”

The summer research experience in Door County reinforced Behrens’ desire to work in environmental science. After learning that the retirement of two Mankato faculty might delay her ability to take key classes she would need to graduate, she transferred to UW Oshkosh.

“I liked the campus and the town,” she says. “The class list offered a lot of variety in the areas I’m interested in.”

Behrens is now in her first semester at UW Oshkosh and is pleased with her decision. In October, she presented her marine debris research at the Great Lakes Beach Association Conference. Next semester she hopes to work in the ERIC lab to gain additional hands-on experience — and she should graduate on time and ready for a career in water.

“I’m in a good spot and should finish in four years,” she says. “I’m not sure of my job path, so I’m taking a variety of environmental science classes. I’m leaning toward water quality but am also interested in toxicology.”

Freshwater Collaborative funding helps to support UW Oshkosh’s efforts to hire multiple students each summer to conduct water-quality field research in Door and Manitowoc Counties, collect plastics and conduct microplastic research, and conduct well water testing at various locations, including the ERIC lab. Interested students should contact Greg Kleinheinz at kleinhei@uwosh.edu. Students from any university are welcome to apply.

No matter the size of the group, though, Hurley said the goal remains unchanged, “The overall goal is to provide immersive student research experiences to enhance workforce development skills and allow undergraduates to consider the option of graduate studies in Wisconsin. Research experience as an undergraduate is an important component of a successful application for graduate school. In the job market, it also sets apart recent undergraduates who have addressed the changing needs of water-related fields.”

No matter the size of the group, though, Hurley said the goal remains unchanged, “The overall goal is to provide immersive student research experiences to enhance workforce development skills and allow undergraduates to consider the option of graduate studies in Wisconsin. Research experience as an undergraduate is an important component of a successful application for graduate school. In the job market, it also sets apart recent undergraduates who have addressed the changing needs of water-related fields.”