Author: Heidi Jeter

Student Spotlight: A Geomorphologist in the Making

When the City of River Falls needed qualified people to provide ecological monitoring for their dam removal projects, UW-River Falls faculty and students stepped in to fulfill this community need.

Thanks to a grant from the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin, Zach Blackert, Environmental Geography major at UW-Eau Claire, was one of six students selected for the Dam Analysis and Monitoring Crew. The DAM Crew is a cooperative effort involving UW-River Falls, the Kiap-TU-Wish Chapter of Trout Unlimited, the Kinni Corridor Collaborative and Inter-Fluve. Read more at Dam Removal Project Opens Flow of Community-based Training and Research.

Here’s what they said about their experience.

Why did you choose to participate in this field experience?

Last spring I took an intro to geomorphology course, and my professor recommended the dam project. Then my mentor suggested it would be a good opportunity for someone interested in geomorphology and river work. I especially liked it being related to environmental restoration and conservation.

What did you learn?

The field experience that we had during class was mostly identifying landscapes and being able to interpret them. We didn’t do much of the data collection like we did with the Freshwater Collaborative project. It was interesting to take the concepts that I learned in the classroom and apply them to the real world.

Working with Sean Morrison at Inter-Fluve, we learned the ways that he or someone in his position would collect the data and how to understand the stream in a specific way. We got a holistic idea of what the river looks like at different stretches and then we learned how to blend that with all the stakeholders involved. My biggest takeaway was that you can do the science, but it’s really important to understand why you are doing the science. That was really groundbreaking for me.

Was there anything that surprised you?

It was surprising how invested in science the community was. Almost every day we were collecting data and we’d run into someone walking a dog or kayaking who would ask what we were doing, and we would tell them about the project. I’ve never been somewhere where people are so into the science.

What was the most challenging aspect?

Consistency. We developed the collection method together. We had the same understanding of what to do but each had a different way to do it. We had to communicate better and rely on each other as a team to present what we found. It’s not like any one person became an expert on all the data. You were a web of people who together had a holistic understanding of the data we collected.

What was the benefit to interacting with students and faculty from a different university and with working professionals?

I love Eau Claire, but there’s something interesting about going to a different program entirely. I met a lot of people with interesting majors and interests. It was a great networking opportunity.

I was the only one who doesn’t live in River Falls and had never been there. We spent a whole day learning the history of the river and being presented with all the previous data. I had a good understanding of what was going on with the river, and I felt like I could have those conversations with community members and other stakeholders about what’s going on.

It was really helpful to have conversations with someone like Sean who’s in a field I’m interested in. I could ask him about what he did at his job and what things he wished he’d focused on in college. It was interesting to see how things work and what employers are looking for. It was kind of like having a professional mentor in a sense.

What kind of career do you hope to go into after graduation? How will this experience help you attain your career goals?

I feel a lot more prepared to enter the workforce. Before I was on the fence about what I wanted to do. This cemented that I want to work with rivers and environmental restoration. It’s great to do the work and meet people — to see that this work matters and it’s worth doing. I got to really see how important the science is to the entire city and the entire watershed. It’s not just doing the science but helping the communities the science is connected to.

Student Spotlight: Using Math to Improve Crop Yields

With a grant from the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin, three undergraduates worked on the “The Crop Per Drop in Sandy Soils Project,” a collaborative partnership between UW-Stout faculty and Chippewa Valley Bean. Faculty and students at UW-Stout are developing mathematical models to help Chippewa Valley Bean and its growers increase their crop yield and decrease their water usage. Read more at Predicting the Life Story of a Kidney Bean.

Here’s what they had to say about their experience.

Anna Hansen, applied mathematics and computer science sophomore from Eau Claire

Audrey Williams, applied mathematics and computer science sophomore from Necedah

Noah Royce, applied mathematics and applied physics senior from Antigo

Why did you participate in this project?

Hansen: I chose to participate in this research project because I wanted to explore different ways that I can use math and computer science skills to solve real-world problems.

Williams: I was looking for a summer internship and got an email that Dr. Wojciechowski and Dr. Skorczewski were looking for students to help them research kidney beans! I thought the opportunity seemed interesting and like something I had never done before.

Royce: At first, I was hesitant as I knew basically nothing about agriculture and plants, but I decided that I want to challenge myself by applying my mathematical skills to a topic I wasn’t comfortable with.

What was your role in the project?

Williams: Anna and I assisted Dr. Wojciechowski and Dr. Skorczewski in creating a differential equations-based mathematical model to predict how much water it takes to grow a 100 pounds of kidney beans.

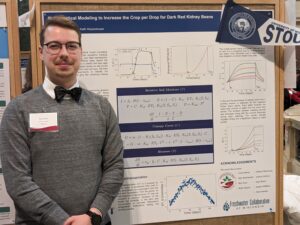

Royce: I added functionality to the model, used computational methods to find parameter values, and I analyzed the model itself to see if it behaved the way we expected it to.

What skills did you learn?

Hansen: From this experience, I learned how to take multiple approaches to a problem as well as how to solve problems as they arise.

Williams: I gained experience in coding in Python, how to efficiently read research papers to understand concepts that are new to me, how to use math to solve real world problems and how to present results to people with less of a math background than me.

Royce: I learned a lot of “hard” math skills, including how to use Python to search for parameters based on given data, and I have new tools for analyzing particularly tough equations. As far as “soft” math skills, I was given a ton of feedback on how to coherently write about mathematics and how to write a compelling abstract. I also got to see firsthand how much collaboration takes place in a research project, which was incredibly exciting and a lot of fun. The most important thing I learned, though, was no matter how good of a mathematician you are, sometimes your ideas just don’t work, and you need to reorient and find a new direction. It’s hard at first, but it gets easier when you realize that’s still progress.

What was your favorite part about conducting this research?

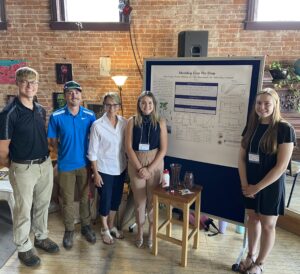

Hansen: My favorite part of this research project was when we presented to Chippewa Valley Bean at the end of the summer as well as at the community forum [at the Raw Deal].

Williams: My favorite part of conducting this research was learning that math research is not just sitting at a table doing math every day. Some days we were out in a kidney bean field talking to farmers with decades of experience farming kidney beans. Other days we were at a farming equipment conference called Farm Tech Days in Marshfield, Wisconsin. If we didn’t have experience in a specific area, we would go to professors in other departments at Stout. It really surprised me how much interdisciplinary work was involved!

How will this experience help you attain your career goals?

Hansen: I am not sure what type of job I want to have after graduation. However, working with two experienced mathematicians all summer helped me develop a sense of what types of jobs I would be able to get after graduation, or what opportunities grad school has to offer.

Williams: I hope to go into data analytics after graduation. This experience has helped me by teaching me how to push through the difficulties of learning new skills. Even if I don’t end up using the specific tools we used this summer, I have a newfound confidence in my ability to broaden my skills!

Royce: I hope to get my PhD in applied mathematics. My passions are research and teaching, so the most obvious career would be a professor. This project made me a far better researcher and a better communicator in mathematics, so this is a fantastic first step toward my goals.

Aspiring Environmental Engineer Gets Hands-on Experience During High School Internship

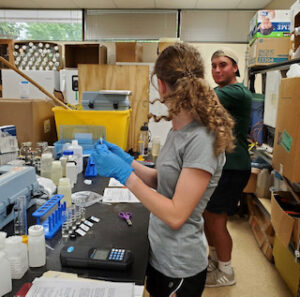

For aspiring environmental engineer Anna Qualls gaining hands-on lab and field experience is an important part of her career path. A summer internship last year was exactly the jumpstart she was looking for.

She conducted stream monitoring, fish surveying and wild rice monitoring; went on field trips to the Farmory and Cat Island; and participated in multiple community events — and she did it all before her senior year of high school.

Qualls, who will graduate from De Pere High School this spring, was the first high school intern to participate in UW-Green-Bay’s Freshwater Summer Scholars Internship Program, which is supported by the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin. The program will expand to six interns this summer.

“I wanted to gain research experience before going to college and I wanted more exposure in the environmental field,” she says. “My favorite part was the stream monitoring and water chemistry because I loved going to the streams to perform physical tests, and I also loved performing water chemistry in the lab.”

The internship program provides high schoolers with opportunities to explore water science and participate in UW-Green Bay research projects. Students are mentored by a faculty or staff member, a graduate student or a qualified undergraduate under the supervision of a faculty/staff member. Current projects include water-quality monitoring in regional streams, laboratory analysis of surface water quality, stream restoration projects, and wetland restoration projects.

In addition to gaining field and laboratory skills, Qualls assisted UW-Green Bay professionals at two Phrag Fests and a Sunset on the Farm event. She also was the student speaker at the Lower Fox River Watershed Monitoring Program Annual Symposium in March, where she encouraged high school students in attendance to consider applying for this summer’s internship program.

“I had an amazing summer. It made me appreciate the environment even more, and it solidified my desire to go into environmental engineering,” says Qualls, who plans to enroll at UW-Madison. “I hope my work as an environmental engineer is for the benefit of the environment and helping to implement sustainable solutions to environmental issues.”

2023 Internship Program Details:

Applications are due by May 1, 2023. The Hiring Committee will review applications and contact selected students by May 8, 2023.

UW-Green Bay will hire six Freshwater Scholars for summer 2023. Students currently enrolled in high school, including seniors who are graduating in Spring 2023, are eligible.

Interns will receive a stipend of $1,500 to participate in 120 hours of active research over the course of the program. Specific projects and activities will be determined by the mentorship team and may take place on any of the four UW-Green Bay campuses. Transportation from campuses to research sites will be provided, but on-campus housing is not provided, and students will need to have or arrange their own transportation to campus. Campus parking pass will be provided.

Join Us at NCUR and Enter to Win an Award to Take a Summer Field Course

Are you passionate about the environment and water? Join us at the National Conference on Undergraduate Research at UW-Eau Claire on Thursday, April 13.

We’ll be hosting a special session and open house with UW System alumni and faculty who are working in water-related careers. Engage with a panel of professionals to learn about careers working with water. Then, stay for our open house to talk one-on-one! Explore our offerings for students throughout the UW System — and enter to win a $500 award toward a Freshwater Collaborative Summer Field Course!

Working in Water Panel, 4:30-5:30 p.m.

Open House, 5:30-6:30 p.m.

W. R. Davies Center – Ho Chunk, Room 320E

Come meet the following water specialists:

- Tina Pint, Vice President/Senior Hydrologist, Barr Engineering

- Kris Benusa, Manager-Environmental Studies, Twin Metals Minnesota

- Marissa Jablonski, Executive Director, Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin

- Sarah Vitale, Assistant Professor, UW-Eau Claire

- Greg Kleinheinz, Distinguished Viessmann Chair of Sustainable Technology, UW Oshkosh

- Rebecca Klemme, Laboratory Manager and Water Resource Specialist

- Maddie Palubicki, Project Engineering Technician, TetraTech

- Brian Hennings, Managing Hydrogeologist, Ramboll

PFAS in Drinking Water: What is the Risk to Your Health Webinar, April 27

The Center for Water Policy will host a virtual Earth Month event featuring its 2022-23 Water Policy Scholar Dr. Laura Suppes speaking on assessing illness risk from PFAS drinking water exposures in Wisconsin.

April 27, 2023, 12-1 p.m. (Central Time)

Suppes is an associate professor of Public Health and Environmental Studies at UW-Eau Claire. She will be joined by her students Alex Barker and Camille Tilden, who are candidates for the bachelor of science in Environmental Public Health. Melissa Scanlan, director of the Center for Water Policy at UWM’s School of Freshwater Sciences, will provide an introduction.

PFAS are harmful chemicals that are being found in many of Wisconsin’s drinking water supplies. These chemicals can cause problems with our organs, hormones, development, and can even lead to reproductive complications. Dr. Suppes’ study assesses how dangerous it is for people to drink water contaminated with PFAS. Her research centers on people in Eau Claire but provides a risk assessment tool that can be customized for other communities.

Predicting the Life Story of a Kidney Bean

Most people don’t know it, but Wisconsin is home to the largest processor and exporter of kidney beans in the world: Chippewa Valley Bean in Dunn County.

Kidney beans are a specialty crop, not yet farmed at the same scale as corn or soy but with the potential to help farmers expand their crop rotation and increase soil health. Chippewa Valley Bean has plans to expand or repurpose 30,000 acres of Wisconsin farmland for growing kidney beans. To do so, the company needs the technology to lower the risk for farmers, particularly in Wisconsin’s Central Sands Region where growing crops can be water-intensive and unpredictable.

Faculty and students at UW-Stout are using mathematics to help Chippewa Valley Bean and its growers reach their goal. Last summer, Professors Keith Wojciechowski and Tyler Skorczewski launched the Predicting Crop Per Drop in Sandy Soils project, with funding from the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin.

Their goal is to develop mathematical models for growing kidney beans — like those that exist for large-scale crops — that will help farmers increase their crop yield and decrease their water usage.

Anna Hansen and Audrey Williams, both UW-Stout sophomores majoring in applied mathematics and computer science, were hired to work with the professors last summer. The students conducted a literature review, coded algorithms in Python, conducted a parameter study, and collected and analyzed data. During the process, they worked with a team of agronomists and growers using mathematics, statistics and computer science to optimize water-use efficiency for growing a crop.

“My favorite part of conducting this research was learning that math research is not just sitting at a table doing math every day,” Hansen says. “Some days we were out in a kidney bean field talking to farmers with decades of experience farming kidney beans. Other days we were at a farming equipment conference called Farm Tech Days in Marshfield, Wisconsin. If we didn’t have experience in a specific area, we would go to professors in other departments at Stout. It really surprised me how much interdisciplinary work was involved!”

Williams says her favorite part was presenting their research at the Chippewa Valley Bean ownership and agronomy meeting and at a poster session for community members held at the Raw Deal in Menomonie, Wisc.

The summer collaboration worked so well that the professors applied for an additional grant to hire an intern to expand upon the work. Noah Royce, a double major in applied mathematics and applied physics, says he was initially hesitant to work on the project because he knew nothing about plants or agriculture, but he wanted to challenge himself. In joining the team, he added functionality to the model and used computational methods to run various watering scenarios that will help identify how to better predict the best frequency and amount of water need to help ensure optimal kidney bean growth.

“We’re looking at the life story of a kidney bean, and farmers want that story to be as boring as possible!” Royce said in describing the project at Research in the Rotunda, which took place at the state capitol in February.

Not only did the Crop per Drop Project provide valuable training to students, but it has led to collaborations among faculty who normally wouldn’t work together. For example, two computer science faculty members built sensors and drones to collect data via Wi-Fi. Wojciechowski and Skorczewski also connected with UW-River Falls faculty to test growing kidney bean plants in their greenhouse. In addition, Wojciechowski says, he can now bring the project into his classroom as a case study to show students how they can apply mathematics to agriculture.

And the partnership with Chippewa Valley Bean is just getting started. Wojciechowski will work for the company while on sabbatical, using applied mathematics to determine where beans are most at risk during growing and processing, develop efficiencies in their processing plant, analyze irrigation practices, and develop a planning plan with field maps so the company can collect data during harvesting.

“Getting the Freshwater Collaborative funding helped us see how this collaboration could work. This project allowed us to start the relationship,” he says. “They liked it and they want to do more. It’s become more than a corporate partnership.”

He plans to bring more students into the research this summer. A group of growers with Chippewa Valley Bean are letting them install temperature and moisture sensors in their fields so the research team can collect real-world data over the next two years. That data will help fine-tune the models. The resulting precision agricultural tools will lower the economic risk for growers who want to expand into kidney bean crops.

Charles Wachsmuth, vice president at Chippewa Valley Bean, says not only will the research help their growers be more efficient, but it will help the company as a whole address sustainability, which is important to their customers.

“The Crop Per Drop Project research is a game changer for Chippewa Valley Bean,” he says. “The ability to share new water management practices with our growing partners has long-term implications as we begin to look at a future with restrictions on normally abundant resources. Not only is this important for our growers, but partnering with UW-Stout on a true sustainability project is important to our customers as well.”

Dam Removal Project Opens Flow of Student Training and Community Collaboration

Flowing through the city of River Falls, the Kinnickinnic River is a class I trout stream that also is home to two dams that have generated the city’s hydroelectric power for decades.

When the River Falls community decided to remove the dams and restore the riverway, the Kiap-TU-Wish chapter of Trout Unlimited and Inter-Fluve, a firm specializing in river restoration, developed an extensive 10-year monitoring plan for the project. The plan was provided to the City of River Falls and the Kinni Corridor Collaborative, a nonprofit that is leading fundraising efforts for the dam removal and river restoration work.

“When the city council decided to remove the dams in 2018, the resolution stated there should be a monitoring plan and ongoing monitoring to determine effectiveness,” says Kent Johnson of Trout Unlimited. “Monitoring the removal of the first dam would inform removal of the second dam.”

Due to budget constraints, the plan initially relied upon volunteers to conduct the monitoring. That created potential challenges in terms of reliability, consistency of the data collected and the ability to provide long-term monitoring.

That’s when an ongoing research partnership with UW-River Falls faculty and staff came into play. Why not use the monitoring project to provide undergraduate students with hands-on training while also fulfilling a community need?

Jill Coleman Wasik, associate professor at UW-River Falls, and Heather Davis, lab manager, requested a grant from the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin to create “The Dam Analysis and Monitoring (DAM) Crew,” a two-week student experience during which working professionals would train undergraduates in monitoring techniques.

“Trout Unlimited and the Kinni Corridor Collaborative wanted scientifically valid data. They couldn’t just rely on volunteers to come in any day and collect data,” Coleman Wasik says. “The funding from the Freshwater Collaborative came at a critical time for the monitoring plan and allowed our faculty and students to meet an identified need.”

Five UW-River Falls students and one from UW-Eau Claire were selected to work on the DAM Crew. Sean Morrison, a geomorphologist at Inter-Fluve and a graduate of UW-Eau Claire, trained them on several technical skills with a focus on data collection, which is an essential skill his company looks for when hiring. During the first week, the students often spent eight hours a day in waders, collecting samples.

Trout Unlimited has been monitoring the impacts of the city’s dams and storm water discharges since 1992, so Johnson shared historical data and demonstrated Trout Unlimited’s macroinvertebrate monitoring as well as a phone app (WiseH2O) the organization uses for water quality and temperature monitoring.

The students weren’t told the dams would be removed. Instead, Davis led them through a process of inquiry during which they were given basic information, made observations at the sites and analyzed data they collected. Students looked at water-quality parameters, temperature and stream ecology as well as legal and economic aspects of the project. They then presented their conclusions and recommendations to stakeholders.

“The students concluded the dams should be removed,” Davis says. “They talked about strategies for dealing with the dams after they’re drained and ways to make a community space that’s healthy for the river and the community.”

Those involved agree the DAM Crew project strengthened connections between UW-River Falls and the community. The university was able to exemplify the Wisconsin Idea by actively participating in a community project, and community partners had the opportunity to work with future water professionals. Students received hands-on training and networking opportunities — and saw how their research could solve real problems.

“It’s easy to do the science but not know if it matters,” says Zach Blackert, an environmental geography major who will graduate from UW-Eau Claire in May. “I got to really see how important the science is to the entire city and the entire watershed. And I feel a lot more prepared to enter the workforce.”

As part of the grant, Jordyn Curtis and Mckenna Kellogg were hired as interns to continue data collection during the spring semester. They also will be able to conduct research into soil cores, sedimentation and vegetative cover, which will further inform the river restoration and lay the groundwork for future student research.

“I’m very appreciative they gave us the opportunity to continue the study from the summer,” Kellogg says. “They trust us with this independent research and believe in us to be able to create a framework for future interns.”

Curtis adds: “We’re pioneers. It will be good for future students, and I think it’s good it’s here at UW-River Falls.”

The goal is for the DAM Crew to conduct river monitoring each summer and provide ongoing data and recommendations to the community partners.

“It’s very rare that we’re able to do anything beyond photo monitoring. Monitoring is always one of the first things to get cut from the budget,” Morrison says. “The Freshwater Collaborative funding did a great job of helping to train the next generation of water resource professionals, and it provided us with a dataset that will provide really unique insights.”

Steering Committee Meeting March 29

The Freshwater Collaborative Steering Committee will meet Wednesday, March 29 from noon to 1:30 p.m. via Zoom.

Agenda

- Certificate Market Research updates

- Legislative Bill Update

- Summer courses and programs

- RFP proposal deadline

- Upcoming Events

- Freshwater@UW program

Zoom link: https://uwm-edu.zoom.us/j/6521525400